For skiers across the Western U.S., the 2024-25 season has been a tale of feast or famine. In one corner, the Pacific Northwest and Northern Rockies have rejoiced in fairly frequent storms and healthy snowfall. In the other, the Southwest has been left high and dry, watching storm clouds bypass overhead. One culprit behind this powder disparity is La Niña–a climate pattern known to tip the snow scales–which arrived fashionably late this winter and dealt very uneven hands to different regions.

Announcement: March 1 the 2025/2026 Indy Pass goes on sale until they sell out! Don't wait because they do stop selling the pass once sold out!

Awakening a Shy La Niña

La Niña, the cool-water “little sister” of El Niño, took its time coming to life this season. Sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific didn’t definitively dip below the La Niña threshold until December 2024, making for a late-developing event. Once it awakened, though, La Niña’s influence on the atmosphere kicked in with gusto. By mid-winter, the ocean’s cooling remained weak, but the atmosphere responded as if La Niña were in full swing. This unusual ocean-atmosphere mismatch helped shape our winter in subtle but significant ways.

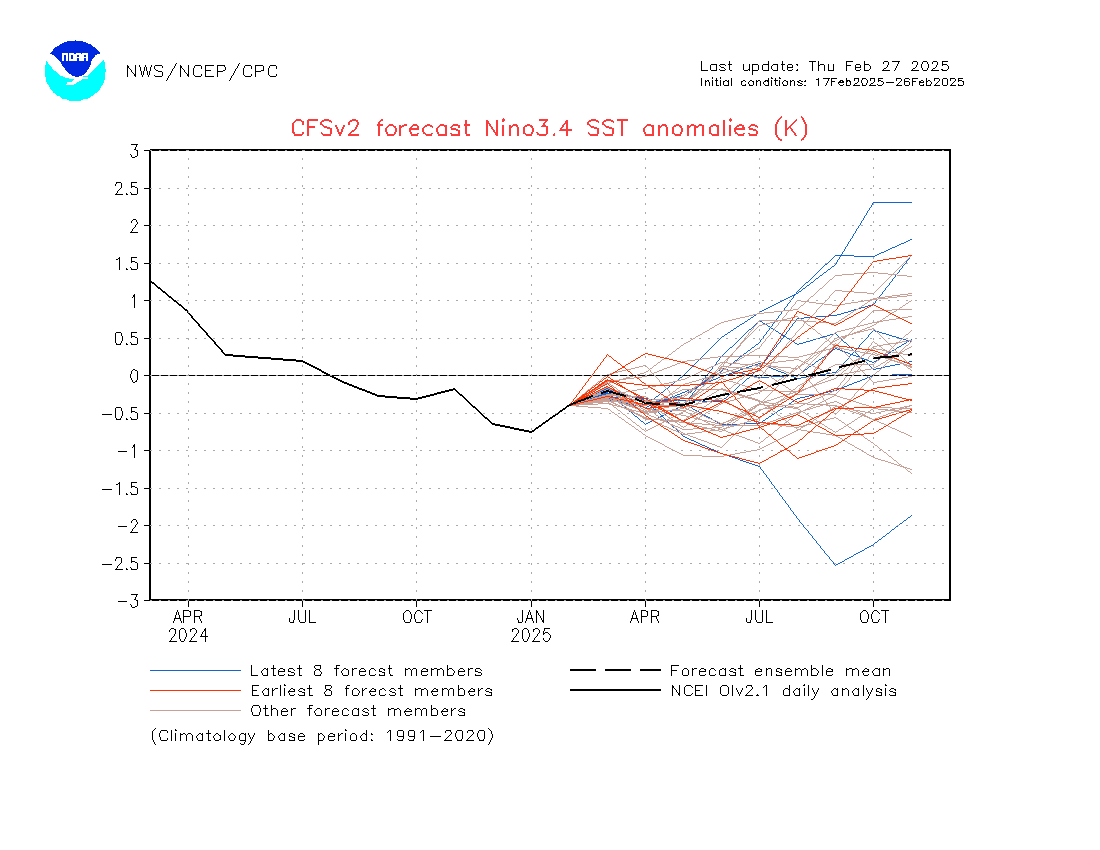

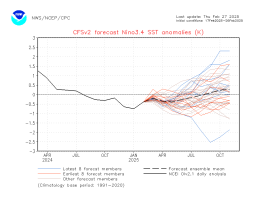

The last year of ENSO conditions. The most reliable indicator here is Niño 3.4, which accurately reflects the weak La Niña we've seen this year.

From the outset, climatologists predicted this La Niña would be a brief guest rather than a long-term lodger. NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center officially hoisted a La Niña Advisory in late fall, but emphasized it would likely be short-lived. Sure enough, as of mid-February, La Niña conditions were still present but are expected to fade through the spring, with a 66% chance of a transition to neutral during March–May. Essentially, La Niña showed up late, has made some mischief, and is already eyeing the exit. The window for classic La Niña impacts was narrow–just a few months in the heart of winter–but as Western skiers can attest, those few months have made a world of difference on the slopes depending on where you ski.

The North-South Snowfall Split

When La Niña is in play, it often orchestrates a very polarized winter across the West. This season has been no exception. La Niña tends to energize the winter jet stream in a way that favors the Pacific Northwest and northern tier states with the most consistent snowfall, while leaving California and the southern tier drier and warmer than normal. True to form, the 2024-25 winter delivered a classic north-versus-south divide in snow fortunes.

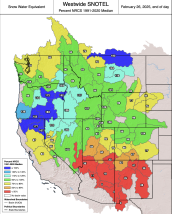

Snowpack versus the 1991–2020 median as of mid-February 2025. Blue and green areas have near to above-normal snowpack, while orange and red areas indicate well below-average snow. Northern states like Montana, Idaho, Washington and northern California are generally in good shape (some basins over 120% of normal), whereas Arizona, New Mexico, southern Utah and southern Colorado are languishing under less than half of their usual snowpack. Credit: NRCS

The current snowpack map tells the story in vivid color. Across Arizona, New Mexico, southern Utah, southern Colorado, and parts of Nevada, an exceptional snow drought has taken hold, fueled by record dry conditions over the past two months. Many areas in the Southwest are sitting at a paltry 30–50% of their normal snow water equivalent. High-pressure systems repeatedly deflected storms away from these regions, leading to weeks on end of blue skies, much above-average temperatures, and hard-packed or bare slopes.

Meanwhile, far to the northwest, it’s almost been the opposite story. A steady parade of Pacific storms fueled by La Niña’s jet stream positioning brought consistent dumps to the Cascades and Northern Rockies. Washington and Oregon started a bit dry in early winter, but a well-timed storm cycle in late January brought welcome moisture to the Pacific Northwest. A few atmospheric river events bullseye’d Oregon and far northern California, pushing their snowpack to above-average levels in places. Parts of the Oregon Cascades and the Sierra Nevada north of Lake Tahoe are boasting 120–130+% of median snowpack–a godsend for those areas considering the broader regional dryness to their south. The Northern and Central Rockies (Wyoming, Idaho, northern Colorado, etc.) have been closer to normal overall, with consistent smaller storms keeping base depths respectable even if no single month was extraordinary.

It truly has been a tale of two winters unfolding simultaneously. La Niña’s fingerprint is all over this pattern: a steady tap of Pacific storms for the northern half of the West, and a stubborn atmospheric roadblock guarding the southern half.

A Weak La Niña Still Packs a Punch

It’s worth emphasizing that this La Niña, while impactful, is on the weaker side by historical standards. We haven’t seen the kind of intense, long-lasting cooling in the Pacific that characterized some famous La Niña winters of the past. Unlike the epic “triple-dip” La Niña of 2020-2023 that spanned three winters, this episode is projected to be short-lived.

Yet even a lightweight La Niña can throw around some weight in our weather. The atmosphere doesn’t always care whether the ocean cooling is weak or strong–sometimes it reacts regardless, and that seems to have been the case so far this season. January 2025, for example, ended up as one of the driest Januarys on record for the United States (even in the PNW), with much of the West parched under dominant high pressure. This occurred despite La Niña’s moderate ocean signal, underscoring that timing and alignment of atmospheric patterns (like the placement of the jet stream and the occurrence of other climate drivers) can amplify La Niña’s effects. In our case, La Niña helped promote a persistent ridge over the West that blocked precipitation, particularly in the Southwest, leading to the snow drought conditions we’ve seen.

On the flip side, when the jet stream did sag southward on occasion, the Pacific Northwest and northern California were ready to cash in. One or two moisture-laden storms in a La Niña winter can mean the difference between bust and bounty for those regions. We saw that with the late January atmospheric river that unloaded on the Oregon Cascades, bringing multi-foot snow totals and swiftly erasing early-season deficits. It’s a reminder that no two La Niñas are exactly alike–and even a short, weak one can pack a punch if the atmospheric setup is just right.

The Home Stretch: Will March Bring Mercy?

As we turn the corner into late February and look at the remainder of the ski season, many are asking: is there hope for a late comeback in the snow-starved Southwest? And will the northern areas keep getting refreshers? The answer, as usual, lies in what La Niña does next–or perhaps what it stops doing.

The latest model guidance showing warming (neutral) conditions into the spring & early summer, returning to average/just above average by the fall. Credit: NOAA

The latest forecasts show La Niña stuttering toward a finish. The consensus of NOAA, the European ECMWF model, and other forecast teams is that the Pacific will continue warming back toward normal through spring, effectively ending La Niña’s influence. In practical terms, that means the atmosphere’s La Niña-driven pattern should gradually loosen its grip. By March and April, we expect the jet stream to become less locked in its north-biased configuration.

For the Pacific Northwest and northern tier states, this transition likely won’t snatch away all the snow. These regions have banked a decent snowpack, and a weakening La Niña doesn’t flip to El Niño overnight–so occasional storms should still roll through. In fact, a fading La Niña can sometimes open the door to a more variable late-season pattern. There’s potential for the storm track to wobble a bit farther south at times, which could deliver a decent spring dump or two to parts of California, Utah, or Colorado that have been missing out. However, time is running short, and climatology is a harsh referee: March can bring big surprises, but expecting it to singlehandedly erase a season-long deficit in the Southwest might be wishful thinking.

So who could still benefit as the ski season winds down? Likely the same folks who have benefited so far. The Pacific Northwest and northern Rockies should continue to see cooler temperatures and chances for late powder, keeping their season going strong. Higher elevation resorts in Wyoming, Idaho, Montana, and perhaps northern Colorado could see a couple more productive storms before the spring thaw. Unfortunately, those who have been losing out–the southern Rockies and Southwest–may not completely break the pattern in time. It’s hard to imagine Arizona suddenly catching up on a 70% snowpack deficit in March. Barring a miracle “March Madness” superstorm, places like New Mexico and southern Colorado will probably end the season below average. They might luck into a stray spring storm (spring often brings at least one surprise), but even then, warm sun quickly turns spring snow to slush, so beware when chasing.

In short, La Niña’s waning weeks are unlikely to dramatically upend the story we’ve seen all winter. Weak La Niña is still La Niña, and its hallmark north-south split will likely linger in some form through the final weeks of the season. If you’re chasing late-season powder, follow the familiar bread crumbs: go north (or high).

Looking Ahead: ENSO Wildcard for 2025-26

With La Niña on its way out, powder enthusiasts are already gazing into next winter’s crystal ball. Will we see a flip to El Niño (and thus a whole new snow pattern), a continued neutral lull, or an unexpected encore from La Niña? The long-range ENSO model guidance is a bit like an unsettled snowpack right now–layered and uncertain–but it does offer hints at what 2025-26 might hold.

Currently, most expert outlooks agree that we’ll slide into ENSO-neutral conditions over the summer once La Niña dissipates. The equatorial Pacific should hover around average temperatures for a while. What happens after that–into the fall and next winter–is where the forecast models diverge. Interestingly, there’s a split in the guidance from major forecasting centers: the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (which includes NOAA’s models) has been suggesting La Niña could re-emerge later in 2025, essentially a double-dip La Niña, whereas the European ECMWF model has hinted that a weak El Niño is more likely to develop by next winter. In other words, one camp sees a possible return of the cool Pacific pattern, and another camp spies the potential for a swing to the warm side.

Part of the challenge is the infamous “spring predictability barrier,” a period in spring when the tropical Pacific is notoriously fickle and models have a harder time seeing the future. So we need to take any long-range predictions with a grain of salt (or a grain of snow?). That said, we can explore the scenarios:

- La Niña hangs on or returns: If La Niña were to linger or make a comeback for 2025-26, we could be looking at a very similar winter to this one. The Northwest would likely continue its winning streak of storminess, and the Southwest might brace for another rough, dry ride.

- A flip to El Niño: On the other hand, it’s entirely possible the pendulum could swing the other way. A budding El Niño would mean the tropical Pacific warms up substantially, which typically rearranges the jet stream in the opposite fashion. Historically, El Niño winters favor Southern California, the Southwest, and the southern Rockies with more moisture, while the Pacific Northwest tends to dry out.

- Neutral stays neutral: There’s also the scenario that nothing dramatic happens at all. The Pacific could stay in a neutral gear through next winter. Neutral conditions don’t mean bland weather, but they lack the strong push that El Niño or La Niña gives. In a neutral winter, other factors (like the Arctic Oscillation or random jet stream meanders) play larger roles, and the snowfall patterns can be more variable and harder to predict.

For now, all eyes are on the Pacific to see which way it leans in the coming months. The only near-certainty is that El Niño’s odds are currently low for the next six to nine months, so the dramatic flip to a wet Southern U.S. winter is far from guaranteed. We at Powderchasers will be watching the forecasts, and by late summer, we should have a clearer picture of whether La Niña is regrouping for another go, or if the Pacific is warming toward El Niño territory. That’s the point when next winter’s winners and losers will really start to take shape.

Please help us out!

NOTE: Please support Powderchasers with a donation, merchandise purchase (such as a hat or stickers), or sign up for our custom Concierge Powder Forecast Package, where we provide 1:1 phone & email support to get you to the deepest locations possible. When chasing snow, the Concierge gets you the very best intel. Sign up for our free email list so you never miss a powder day. We are also seeking new sponsors and ambassadors who want to submit photos and videos; please reach out for more.